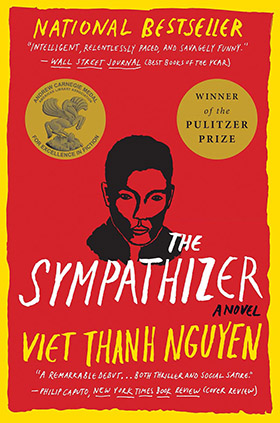

Lily Wong of 8asians reviews The Sympathizer.

Viet Thanh Nguyen’s expertly and cunningly crafted debut novel The Sympathizer dictates a confession in the years after the end of the Vietnam War. At it’s very base, this is a spy’s story. Told from his perspective to an unnamed Commandant (and equally so to the reader), the narrative unfolds from shortly before the so-called fall of Saigon in 1975 when Communist forces took over the city from the Republic of Vietnam.

Viet Thanh Nguyen’s expertly and cunningly crafted debut novel The Sympathizer dictates a confession in the years after the end of the Vietnam War. At it’s very base, this is a spy’s story. Told from his perspective to an unnamed Commandant (and equally so to the reader), the narrative unfolds from shortly before the so-called fall of Saigon in 1975 when Communist forces took over the city from the Republic of Vietnam.

“The Sympathizer” is a man who sees things from both sides, a Communist mole who at times feels conflicting individual loyalties, to people and causes. Though a plot moves the tale along, the true strength of this book lies in the moments where the narrator reasons through his thought process in an almost stream-of-conscious manner that is utterly rational, convoluted, and simultaneously cynical and optimistic–which is to say, incredibly smartly written. From the very first paragraph, Nguyen draws you in…

I am a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces. Perhaps not surprisingly, I am also a man of two minds. I am not some misunderstood mutant from a comic book or a horror movie, although some have treated me such. I am simply able to see any issue from both sides. Sometimes I flatter myself that this is a talent, and although it is admittedly one of a minor nature, it is perhaps also the sole talent I possess. At other times, when I observe the world in such a fashion, I wonder if what I have should even be called a talent. After all, a talent is something you use, not something that uses you.

And so the story unfolds, with the narrator turning his wit against one and all, from the Americans who supported and trained South Vietnamese during the war, to the South Vietnamese generals who hold on to hope beyond hope after being exiled in the chaotic flight from Saigon, to the Communists who dictate the spy’s missions.

Beyond this are minor characters who themselves provide scathing critiques, particularly of American life. For clearly biased reasons, I found particular snark and strength in a Japanese American secretary the narrator meets while in exile in Los Angeles after leaving Vietnam. Ms. Mori, a nisei, relates strongly to the life and ambiguities of a spy:

For a long time I felt bad. I wondered why I didn’t want to learn Japanese, why I didn’t already speak Japanese, why I would rather go to Paris or Istanbul or Barcelona rather than Tokyo. But then I thought, Who cares? Did anyone ask John F. Kennedy if he spoke Gaelic and visited Dublin or if he ate potatoes every night or if he collected paintings of leprechauns? So why are we supposed to not forget our culture? Isn’t my culture right here since I was born here? Of course I didn’t ask him those questions. I just smiled and said, You’re so right sir.

It is this kind of biting and dark humor that pervades the novel to varying degrees of strength, and in these moments, the author finds his unique voice and propels the reader through the pages. His woven-in critiques of American culture and war making and society are refreshingly stated, never too simplistic or overblown.

Wrapped up in this unfolding tale of a country divided are three childhood friends who made a blood bond in the innocence of youth, and who were themselves than divided over their political sympathies and loyalties, mirroring their own country, each grappling with questions of freedom and nation and loyalty. As much as anything, they are the center of this story, and it is this friendship that causes the most trouble for the intelligent sympathizer who sees all sides. The fates of this trio are made known by the end of the novel, resolving certain elements of plot, in a manner somewhat out of style with the rest of the book. It is less the substance of these “conclusions” and so much more the meat in the rest of the book that are compelling.

The Sympathizer has been widely hailed for bringing specifically this new voice to the body of work around the war. And though this is a novel about the Vietnam War and its aftershocks widely different from other works set within this tumultuous half century in Vietnam’s history, it is equally about that abstract thing called human nature, about how a mind plays out its conflicts and the consequences of our decision making. It is the kind of book that bears reading more than once.