Host Philip Nguyen gets into it with the Captain himself, Sympathizer star Hoa Xuande. They talk about leaning into opportunities, navigating multiple cultures as children of Vietnamese refugees and what it was like for Hoa to be in nearly every scene of the show. Philip also sits down with Executive Producer Amanda Burrell to talk about casting the show – and scouring the globe for talent such as Hoa. And, of course, we are joined by author of the novel The Sympathizer, friend of the pod Viet Thanh Nguyen about how the episode matches up and diverges from the novel for HBO

Read Below for transcript.

INTRO

PHIL: Welcome to HBO’s, the Sympathizer podcast where we are

debriefing and decoding the new HBO Original Limited series, the

Sympathizer, which is based on the Pulitzer Prize winning novel of the

same name. I’m Philip Nguyen , a scholar of Vietnamese American culture,

and on this podcast I’ll be joined by the sympathizers creators, the cast and

crew, and of course, author Viet.

After every episode, we’ll go deeper into the characters, their motives, and

how this espionage thriller slash cross cultural satire complicates what we

know about the Vietnam War, a. k. a. the American War in Vietnam, and

its depiction in U. S. pop culture today. Looking at you, Hollywood.

<>

But, before we get started, there will be spoilers.

So go and watch episode 2 exclusively on Macs before listening. To the

podcast.

<>

All right. All right. All right. Let’s get started today. We’re diving into

episode two. Good little Asian with executive producer, Amanda Burrell.

Then, we’ll get a sneak peek into how actor Hwasun Dae becomes the

captain, and his process to become such a complex and multi layered

character.

And finally, we’ll sit down with the author of The Sympathizer, Viet Thanh

Nguyen, about this episode, and how it’s similar, but different. Or different

from his novel.

<>

So, a lot happens in this episode. Before we talk with some of the cast and

creators, here’s a little recap and a bit of historical context for episode 2

that I think will help us understand some of the action and thinking behind

the characters motives. The episode opens to reveal that Bon and the

Captain are on a road trip across the American West.

But before that, they were at a vermin infested refugee camp with the

General.

<>

For Vietnamese refugees fearing for their lives forced to flee, Operation

New Life offered well just that, a new life in America with just a pit stop in

Guam for a few weeks. Where the American military process, tens of

thousands of refugees.

Operation New Arrivals flew refugees to one of four military bases

stateside. Fort Chaffee in Arkansas, Camp Pendleton in California, Eglin

Air Force Base in Florida, and Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania. Where

our author, Viet Thanh Nguyen, was processed at the age of four.

In this episode, we also see the captain out in the world living in L. A. First,

he heads back to Cal West College, where he was once a student and now

works under Professor Hammer, who’s played by Robert Downey Jr., and

his assistant, Miss Mori, played by Sandra Oh, in the Oriental Studies

Department.

<>

It’s at this party that the captain and Miss Mori begin to bond, or rather,

grumble over the professor’s overt and subtle racism. And they also start a

physical relationship, after the captain shares a particularly teenage

moment he had with a squid.

Meanwhile, the general and his family have finally left the refugee camp in

Arkansas and resettled in a run down home in L. A. We see the general’s

paranoia about a spy continue to set in. taking up alcohol to cope, first by

drinking, then by selling, when he opens a liquor store nearby.

At the festive opening of the General’s Liquor Store, the captain reunites

with Sonny, a former classmate of his at Cal West and now a journalist

with progressive personal politics.

As the General continues to put pressure on the Captain to root out the spy,

he’s forced into a corner, eventually suggesting that Major Wan, also

known as the Dumpling or Bun Bao, is up to something.

The general agrees and the episode ends as the captain recruits Bon to

assist with the mission. Take down dumpling.

<>

Our first conversation is with producer extraordinaire Amanda Burrell.

Amanda is currently the president of Team Downey, working alongside

Robert Downey Jr. and Susan Downey. I’m so happy to welcome Amanda

to the podcast.

<>

PHIL: What was some of the most challenging aspects of dealing with

this story and the way that it calls into question or disrupts a lot of the

conventions of how people, especially in America, pop culture, media,

the government think? What was that like for you?

AMANDA: Well, uh, You know, as a white American, I learned about

the Vietnam War as America’s kind of greatest tragedy and ego hit and all

of the big massive loss. And really only heard it from that point of view,

obviously. And, you know, for us, the book and the script got a tone that

also recognized the absurdity of it all. That war at this, you know, as

tragic and horrific, and obviously at the end of episode one, you are left

bereft and crying, and But there’s also kind of a strange. Like, what is

going on?

How does Claude show up and sing a song in the middle of this tarmac

when people are about to leave? But what else are you left to do as a

human? And so, I think that mishmash of just real humanity at the core of

this is what really excited us, is how do we really kind of create that tone

that allows for those spaces.

PHIL: Right? Yeah. And it’s, it’s funny. It is. I mean, not to say that the

war or its aftermath were funny, of course. Right. Um, but in the way that

it is, you know, very, it’s, it might trigger a lot of trauma for some folks. It

deals with very serious topics. There is this, this, this sense of, but we can

laugh at it. At the same time, the another layer of complexity, since we’re

peeling back some of the layers of this onion, that is a series, you know, is

that we’re, we’re being told the story through this, uh, the slipperiness of

the narrator’s memory to the captain’s memory.

AMANDA: Yes, yes.

PHIL: There’s flashbacks and flash forwards that are happening.

AMANDA: I think that’s a really valuable point because, especially

Robert’s characters, there’s a heightened nature of them, you know,

because it was really his point of view, the captain’s point of view, and so

I do think, you know, the captain’s wrestling with the fact that obviously

his, what his allegiances are, um, But America is seductive, capitalism is

seductive, so we can’t judge it. He, he’s being pushed and pulled and, and,

and doesn’t really know where to fit because it is seductive for lack of

better, you know.

PHIL: Yeah, and I mean, I feel like as a, as an audience, like as someone

who’s watching the series, you know, we, the, the sympathizer as the title,

we are kind of, are we the sympathizer ? Right? Um, is it the captain? Is it

the people who he’s like interacting with and engaging with and in the

time that he’s in the United States, you know? Um, yeah. So the, the meta,

the meta ness of the, of the series is, it, it’s, it speaks for itself. Quite

profoundly and I feel like that really begins to sink in in episode two

AMANDA: Yes. Well, and the high low of it too, the, the, the refugee,

uh, Um, obviously Camp Fort Chaffee was really specific. Then there’s

just the breathtaking West that, that Director Park really wanted to

capture. I think he was really excited about just the wide open spaces that

America provides.

PHIL: Like Americana, the promise of the American Dream. Yeah.

Exactly.

AMANDA: And also I think Vietnam is wet and, and, you know, there’s a

different like humidity in the air. And this was just America, which is, has

a kind of. Desert, dry, just a totally different vibe. And so we really

wanted to, to contrast that, the episode one to episode two.

And then after that, it was also about the contrast of these glamorous

spaces, the parties, the whatever. And then his, their home, you know,

him and Bon, home and, you know, and in these motel rooms that aren’t

the most glamorous side of America. So it’s kind of, those contrasts were

really clear.

PHIL: Yeah. Oh my goodness. The different layers of what America is

for different people depending on who you are. Exactly. Um, and how our

our narrator, our captain, is kind of navigating through each of these

spaces. Yep. Um, with all of the baggage that he’s bringing with him

from, from Vietnam.

AMANDA: Well, and the tragedy, and Bon sitting there, absolutely

bereft, beyond, you know, um, I think he’s, oh, he, Bon is the constant

reminder of that.

PHIL: Right.Oh, I really appreciated the, uh, the altars, um, to the, to the,

the, the lost. I feel like that was very, it, it, there was a sense of cultural

resonance for me, um, in seeing that and it evoked a sense of, like,

Vietnamese American ness, especially as, as folks who were, knowing

that, like, folks like my parents were displaced from their homes and

trying to find a home in a, in a, uh, a distant land was not, not always the

easiest.

AMANDA: No. And also I, I mean, I, I’m really glad to hear that because

so much of what we were. Uh, you know, what we really needed to do

was get this right. Like this has, and all of our consultants were

incredible. So many of our writers were, just everybody brought

themselves to it. Even our actors, I would say the, the most kind of

amazing thing about the casting process too was how many actors

brought their own experience and, and actually after being cast, were able

to have conversations with their parents that they didn’t.

It’s like, it was like a project that, you know, that my parents had never

had before. Or they would read the, they read the book just in preparation

and were like, Oh my gosh, I now understand my parents. I now

understood, like it was like this illuminating emotional experience for

them. And then bringing that into the show is just, I mean, we used every

bit of it.

PHIL: Yeah. I mean, you’re reading my mind, Amanda . I, the, the next

question that I had was about, about the casting, because this is also one

of the first times in, you know, history that we’re seeing Vietnamese, uh,

Vietnamese Americans and also Vietnamese folks in diaspora playing

these Vietnamese American diasporic Vietnamese roles.

Um, could you shed some light into what that, this, this huge casting call

across the globe was like, and how you landed on the, the folks that we

see in the series?

AMANDA: I mean, well, first of all, I should say the thing that was so

clear from Jump was how many unbelievable actors there are out there

that just haven’t been centered and haven’t been given the opportunities.

The hardest thing was narrowing it down But it all started with our

captain, you know, we knew we had to get him

PHIL: How did you land on Hoa? Yeah.

AMANDA: Oh, man. Um, it was, it was really hard. I mean, first of all,

he, he came in very early and we all fell in love with him because he’s so

soulful and quiet and thoughtful and brilliant.

And, he was going to be the face of the show, and Robert always said, he

was like, I’m not first on the call sheet. The captain is first on the call

sheet. So it’s really, it took a lot, um, he read a lot of times.

He did a lot of callbacks. He met with Director Park in Seoul. He came

out to L. A. Um, there was a lot of conversations with HBO. But

honestly, at the end of it all, it, we all just looked at each other and were

like, it’s him. And also, Hoa has such a gentle, um, spirit as like an

Australian surfer, you know? Um, so when you’re like, you meet him,

you’re like, Oh, wow. But then when he was steely and stoic and he could

turn that on and there’s a mystery to him that I think for us, you know, the

captain had to project.

This confidence and this diligence, but be smushy and vulnerable inside

as he’s wrestling with all these things. And he just, he just had all of it.

PHIL: Especially in episode two when he’s you know, the betrayals start

to happen um, we start to see some some darker sides to to Hoa and um to

to some of our other characters as well Um, I I want to ask you also about

I mean while we’re on casting and the characters the blood brothers

AMANDA: Ugh, I mean, it’s so interesting because Fred also we saw

early in the process and

PHIL: Who plays Bon?

AMANDA: Yes, who plays Bon. And he was absolutely, like we were

very focused on someone who could be very physical because he

obviously has to be a stuntman, like he has to have like a physicality.

He was a war hero.

PHIL: and I think

AMANDA: we missed [00:17:00] that he was going to be such an

incredible emotional center of our show. We knew that we wanted that

character to be that. But once we saw him and Hoa together, it was like,

oh my gosh. These guys have such a deep, deep connection. And then he

happened to be Best friends and see who is like we who is one of our

final casting man was the hardest in a lot of ways he had to play so many

layers, he had to be so many things and Their connection was so vital and

when he got cast and we’d heard that they were friends, but we didn’t

know how close they were

PHIL: Um, it

AMANDA: It all just made sense

PHIL: Episode two also introduces us to some very strong women

characters as well, what was that like for you to work with them?

AMANDA: I mean, they were just. They were incredible because I think

what’s interesting about the show in episode two and the women is the

women see things very clearly. They see it clearly. A lot of the men are

clouded by their own psychological ego, what macho, whatever posturing

that you see. The women Are very clear and they know what they have to

do.

And you’ll see Madame, especially as as the series goes on. She she wants

to take care of her family. She wants to have the pride. Um, and working

with with her. She kind of inherently brings all of that.

She’s she’s so present. She doesn’t have to even say a whole lot. She’s so

present and and just has that power. And then Sandra. I mean, She

breathed a whole level of life into the show. You know, we started

shooting episode two, which is kind of unconventional, because we shot

episode one in Thailand at the end.

Um, so she kind of kicked us all off, I think, especially from a tonal

standpoint. She allowed us to laugh, and when she and the captain Are

talking about that crazy squid story [00:20:00] and

PHIL: Mm-Hmm. Their chemistry starts building. Mm-Hmm.

AMANDA: and the chemistry is odd there. The fact that she’s turned on

by it is, is a whole other layer, which is just so fun.

Um, she, and, and she just brought that to set. Everybody laughed around

her. She just, just made everybody comfortable. So it was.

PHIL: I want to thank you so much for joining us for the official

companion podcast.

AMANDA: Thank you.

Now we’re joined by our protagonist, the captain. Hoa Xuande is an

Australian actor of Vietnamese descent, best known for his roles in Cowboy

Bebop, Hungry Ghosts, and Top of the Lake. He plays the captain in The

Sympathizer, and we’re going to learn all about how he became, as some

would say, a man of two faces.

<>

Can you tell us a little bit about I mean what this moment feels like for

you, right? I think for, for me as a child of refugees myself, uh, being

born and raised in the united states It feels like Vietnamese, like the

diaspora, this is our moment in the spotlight, right? And you are there in

the spotlight. Sometimes literally as we’ve seen in the first couple of

episodes, um, is it something that you think about?

Do you feel it?

HOA: Yeah, when I was taking on this project, I felt the gravity and the

weight of. the expectations of so many people who, uh, of Vietnamese

descent who will watch this and would want this story to be portrayed in

a way that, you know, hasn’t been necessarily portrayed before.

Um, you know, it wasn’t about me. It was just trying to do the best that I

could to hopefully make those people finally feel like that they were

finally represented.

PHIL: And I, I mean personally I feel you do a great job. you. know, just

to Just to gas you up a little bit.

HOA: that’s one. No, I’m joking. Yeah, thank you so much.

PHIL: Um, do you, do you see any similarities between yourself and, uh,

the unnamed narrator in the book, but the captain that you play in the

series?

HOA: Look, I It’s such a deep and profound journey.

And it’s so philosophical as well, you know, especially the captain’s

journey of his dual identities and his, um, beliefs and what ultimately

makes a good human being. Um, will he make his mother proud? Will,

you know, he’s loyalties to his friends. Like, what does that mean to him?

So, um, these are questions that I’ve felt really deeply and connected to

when I read them. Um, cause I felt like I, I struggled a lot with that going

up, even in Australia, like being of Asian descent, let alone Vietnamese

descent that I were,. I grew up in a, in an area and in a place where I

didn’t see a lot of myself. And so, you know, I, I felt a lot of the time I

was reaching to be more Australian, whatever that meant. Um, uh, and I

did things in a way that would make me seem more Australian. Um, but

then obviously I was never, that enough and then, you know, but I never

felt Vietnamese or even Asian enough to be considered that.

So a lot of that was just trying to figure out who I was. And I related to

the captain’s story so much in that way.

PHIL: Mm-Hmm. What was your experience like with the Vietnamese

community in Australia?

HOA: You know, um, there, there is a huge Vietnamese diaspora in

Australia. I, um, I was born in Sydney. Uh, and then at the age of three,

my parents relocated from Sydney to Melbourne. I, I felt like my parents

just removed me from a lot of the Vietnamese, uh, uh, community at the

time because they were just chasing work. You know, when you’re a

refugee, you’re an immigrant, you’re trying to make a living and you’re

just chasing work wherever that may be. And so they moved to

Melbourne simply because they wanted to find work and opportunities

were there for them.

And so I was removed from the Vietnamese community quite early on.

And I grew up around an area that was just full of Australians, a lot of

Greek Italians. Um, and you know, growing up, my, a lot of my

friendship circles and full of, uh, other people other than Vietnamese

people or even Asian people. Um, and it, yeah, you know, when you’re

young and you’re growing up, I’m sure you can relate to this, or a lot of

people can relate to this. Uh, you know, your parents are always

blabbering on about how hard things were in the war and blah, blah.

PHIL: All the things that they went through

HOA: Right. Yeah. All the hardships and how lucky we were and how

like.

PHIL: all the sacrifices that they made

HOA: and how we’re just not appreciative of anything and how, you

know, how, how selfish we all were and, you know, and, you know, I

remember my father and, you know, even my mom just telling us stories

about things that they went through, um, and, and I never took them

seriously and I never really paid attention to it because again, it’s, it’s, you

know, I hate to say, but it’s one of those things when you’re not

comfortable in your own skin, you don’t feel like you relate to it. So these

stories that, that are essentially part of who you are, you don’t relate to, so

you don’t really want to involve yourself with these stories. And it’s really

later on in life that I, you know, through, I guess, figuring yourself out,

being more comfortable with who you are, that you start to pay attention

to what these stories are and mean to you, um, or even just mean to them.

Um, and through obviously doing this show, um, I, I tried to connect

more with what I remembered what those stories were that my parents

told me.

Yeah.

PHIL: Yeah. And in this show, this very historic show, we have a, uh, a

Vietnamese cast, right? Being able to portray and tell this, this very

Vietnamese story um, across diaspora.

HOA: Yeah. All too often when we talk about the Vietnam War and we

portray that on screen as we have for, you know, all the time when we

talk about it, um, in Hollywood, really, uh, Vietnamese people are,

they’re, you know, either, you know, where the, the, the villages that are

seeking help and, you know, we’re trying to be saved or where the

Vietcong, you know, and, you know, where one or the other, we’re not

people who have actual stories or are in positions to lead or are in

positions To affect change in a story where just like the, the

PHIL: getting massacred or murdered.

HOA: exactly doing the massacring or being massacred. Um, so I think it

was really important and really just, uh, a profound moment, you know,

to, to have a story like this that actually puts Vietnamese, uh, characters.

at the center and the forefront of telling this story.

PHIL: So getting into the character, like being the captain. in Those sorts

of roles, right. Knowing the sort of ideological differences that you’re,

you’re faced with these conflicts. Um, can you talk a little bit more about

that, right, As, especially in this moment where you’re a communist spy,

but now you’re a refugee right. And just trying to like survive. What was

that, what was that, um, that pro that research process for you like?

HOA: Yeah, sure. Okay. Yeah. I, so, you know, I think when I was

approaching this character, cause this book on the, on the surface of it all,

it’s a spy thriller, right?

It’s a espionage thriller. It’s a guy who’s playing two sides and he’s like,

am I going to survive or am I going to not? And I think a lot of the times

we see spy tropes as just a guy with a gun running around shooting

people and then hiding in the, in the shadows. And that’s. Basically it and

I really wanted to avoid that I really wanted to avoid just the the surface

level tropes of what a spy was I really wanted to get to the humanity of

what this character, this person was And so I felt like I needed to connect

with this person emotionally deeply on a psychological level So I really

wanted to understand the war. I’ve heard stories. I’ve heard depictions.

I’ve heard my parents tell stories of the war, but I really wanted to get the

facts, the people who were really involved, accounts, uh, people who

could really tell stories of what it was like on the ground during the time

and what, how, what their fears were and what their allegiances were,

what their thoughts were, the psychology of that all.

So I did a lot of deep diving, reading articles of the time, Vietnamese

more so than just, you know, literary historians, um, you know, who are

from the comforts of their home. In the West, right? I really tried to get

Vietnamese perspectives and I actually stumbled upon a real life character

that this character is based on, that Viet borrowed from, and his name is,

uh, Pham Sinh Anh, um, and he was a real life spy from the North, uh,

who, uh, I did a really deep dive on and I watched this 10 part

Vietnamese documentary

PHIL: Ken Burns’ document Oh

HOA: About him.

PHIL: Bout him. Oh, wow

HOA: And, and he was alive at the time when they made this

documentary.

So I could actually hear and see him speak. Um, and so It was really

inspiring. It was actually really inspiring to watch that documentary, to

see a real life person having to, you know, portray, to, to live this life.

Um, and, and all the stuff that you, you sort of read in this book. It’s all

feasible, that he had to really walk this tightrope between playing his part

for both sides, feeding information, um, you know, things that he did and

said in moments that he thought he would literally be the end of it, um,

Things that he would do, you know, he would like wrap up, you know, his

intelligence in film roles in like, um, you know,

PHIL: yes.

HOA: paper rolls. And, uh, yeah, yeah. And then he would set, put it in

the mail and then he would have like handlers pick it up and walk it like

42 kilometers to like the nearest tunnel and then have it passed on to

somebody else. And none of these people knew who they were. They

were all assigned. Uh, codenames and this character’s, uh, it’s not the

character, but the real life person had a codename of X6 and he would

hand it, hand these intelligence roles to his handler B2 and then they

would hand it on to another person called A4 and that’s all they knew of

these people.

They were just kept completely separate, but they were all driven towards

a common cause. It was just really inspiring when I found these stories.

Yeah.

PHIL: Oh my goodness.

HOA: Anyway, I could go on about it, but

PHIL: Yeah, um, at the same time, uh, in episode two, we are introduced

to, a very asian american context. right? um at cal west college. Um, we

meet the professor who is another iteration of Robert Downey Jr. And

we’re introduced, right? We’re, we’re introduced to um, Your love interest.

HOA: Yes Yeah, yeah Yeah, my love

PHIL: Right. What was, I mean, what was it like to build the

relationships with folks like Robert Downey Jr and Sandra Oh, yeah.

HOA: Um You It’s so funny because I met them on my fourth day of

filming. Um, I’d met Sandra before in a rehearsal. And let me tell you,

Sandra Oh is just the most beautiful person. bubbly, eccentric, uh, lively,

bright person that you’ll ever meet.

Like she is exactly the way that she is on screen as she is in real life. And

so I just felt immediately taken into her warmth and, um, I say this a lot

about.

Uh, Sandra and Robert is that, uh, Sandra kind of mothered me. She like

spoke up on my behalf. She was really lovely. Cause she knew how green

I was on a set like this big production, a guy that’s never done, you know,

something on this level before. And I was just really trying to do the best

that I could and not rock the boat.

And Sandra felt that from me. And so she would always step in and be

like, do you need anything? Is there anything that you’re concerned with?

Is there anything that I can do? Talk to the producers on your behalf for,

and, um, and she did that. So I really appreciated that. And Robert is, was

just like the, the, the silly goofy father that I never had.

Um, he, he kind of just came on, uh, On the fourth day of filming. And

that’s when I first met him. And, um, he was already in disguise in a

costume and he was Claude at the time as well. Um, and I just remember

him just like wrapping his arm around my shoulder and just, yeah, just

being really down to earth, and, uh, making me feel like I could just, Do

and say anything that I felt like.

And so that was really nice and warm of him and, uh, and open to just,

uh, taking me in, giving me advice and all that sort of stuff. So yeah, he

fathered me in that way. Yeah.

PHIL: It’s that’s so interesting. I mean, that’s it’s so lovely to hear. I mean,

the, the sort of camaraderie that you had y’all had on set, right? Um, and,

and opposite of that, right. We see the captain navigate these spaces

where. He’s almost being, I mean, along with Miss Mori, right? He’s

almost being like objectified, objectified or even fetishized in a way. by

some of the, the, The Patriarch white patriarchal characters, right? Yeah,

yeah. Um, how, how, how did you have to, how did you navigate that?

HOA: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Um, it’s funny because You know, the

professor is such a character, like I don’t even know how to describe it.

As a representation of the, the, the educational establishment of America.

If you want to put it that way, the cultural establishment of America, you

know, it’s, it’s this, um, white guy who obviously has an obsession with

the Japanese culture and Asian culture in general. And it’s like, he’s

dictating to us what we should be. And, you know, if it wasn’t so sad and,

um, you know, anger inducing, it’s actually. Quite hilarious to think that

he literally categorizes in, in his studies of us in a certain way that he

teaches it to everybody, that this is just what we are. Um, and you see that

in Miss Mori’s reactions.

To him and then you see, in my characters, uh, reaction to how he

behaves around both of us. Right. Yeah.

PHIL: And, you know, later in the episode, um, in episode two, we are

then introduced to the Vietnamese American community. in The liquor

store. Um, that the the, alcoholic general has now opened, right? We’re

also introduced to Sonny for the first time, your arch nemesis. or your

rival

HOA: Yeah. Um, yeah, it’s, that’s interesting. Um, you know, the, cause,

and I think we get that in the depiction at the liquor store of the general,

but you know, the general is supposed to be a divisive figure, he’s not

supposed to be a lovable, uh, you know, Um leader of the time, you know,

in the community, let alone the world, like in the community, he was very

divisive people held him to the account of the fact that he.

It was the representation of the loss of the war. Um, and so for many

people, his promises just never stood. added up. It never stacked up. And

so the grumbles in the community, uh, I’m sure I felt early in the refugee

camp, but it really comes to fruition there when he’s giving this big

speech, you know, to moving on and trying to make ourselves better.

And, you know, that we, we can rebuild again, you know, and we see

people leaving

PHIL: Walking out of his speech.

HOA: yeah, Walking out of his speech.

PHIL: And as we wrap up the second episode of the Sympathizers

Companion Podcast, um for for you Hoa, Um what has been The most

surprising aspect of working on the series, um, so far.

HOA: uh, um, look, uh, apart from, apart from just, you know, it, it, it

does feel like a dream come true to be able to do a project like this on this

level, on this scale with the people that are behind it, honestly, uh, it’s,

you know, never in a million years, what I’ve thought I’d be sitting in this

position to be able to do something like this and to be able to tell this

story, to be able to, to be even able to speak about it in this way. So that is

just, has been surprising to me literally for the last two years.

PHIL: Right,

HOA: Um, but yeah, I think the thing that I’ve learned most about doing

a project like this is that there’s so many.

There’s so many people who are looking forward to, to a show like this

that I know from personally, simply because they haven’t felt like stories

like this have ever been told and the Vietnam War has never really

represented them.

And so they’re really looking forward to a story like this coming out that

is finally, and hopefully being able to tell a certain perspective of the

stories that they’ve never been able to tell.

PHIL: And thank you for that. And with that,

cut.

Interview out HOA

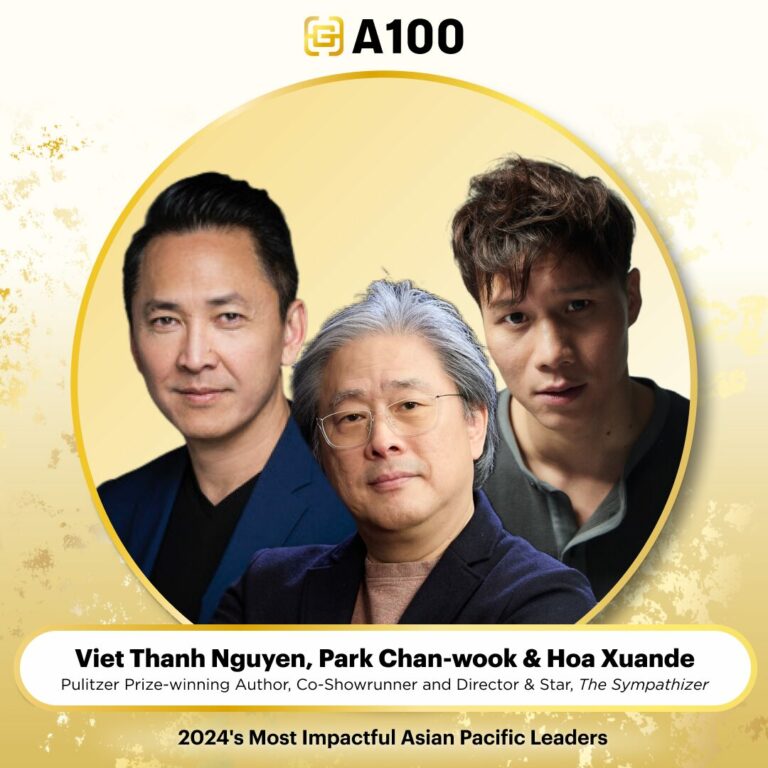

Our next guest needs no introduction at this point, but I will give one

anyway, as without him, we wouldn’t have The Sympathizer as a book, as

an HBO Original Limited series, or this podcast. Viet Thanh Nguyen is a

Vietnamese American professor and author. The Sympathizer is based on

his Pulitzer Prize winning 2015 novel of the same name.

Viet was born in Vietnam and raised in the United States when his family

came as refugees in 1975. He is a professor at the University of Southern

California, a MacArthur fellow, and a New York Times bestseller.

Throughout the podcast, we’ll invite Viet to talk about his novel, it’s HBO

adaptation, our nameless protagonist, a man of two faces, and what Viet

means when he says that “All wars are fought twice. The first time on the

battlefield, the second time in memory.”

Interview IN VIET –

Viet, um, my first question for you about episode two, where we The

captain and the crew are making their way to, to the United States, um,

the rest of the cast is introduced in this episode. There are some scenes in

this episode that I feel like really spoke to me and my experience in the

Vietnamese American community, um, could you speak a little bit about

how you grappled with this, uh, the, the diasporic Vietnamese

community’s reception of your novel, The Sympathizer, um, and, and

perhaps what you anticipate, um, for this particular episode of the series.

VIET: I grew up in the Vietnamese refugee community in the 70s and

80s, so I think I know their, their history very intimately.

And in fact, uh, the episode begins with the refugees, they have now

become refugees, fleeing from Saigon and ending up in Guam. And in

fact, that was my trajectory too, except that was four years old, so I don’t

remember any of the, of that actual experience. So for me to write this,

the, the, the novel dealing with this part of the TV series was really, you

know, fascinating to do the research about what life was like on Guam

and so on.

And and what the resettlement process in the United States was like. And,

of course, I was resettled, uh, in the United States via a different refugee

camp in Pennsylvania versus Fort Chaffee, which is what we see. in this

episode. But I grew up feeling like I was an outsider in the Vietnamese

refugee community because very instinctively, for whatever reason, I was

always skeptical of the insider position.

So I was very familiar with the insider position for the Vietnamese

refugee community that it was very anti communist, and it was being led

by these exiled political and military figures uh, from the South

Vietnamese government and military, and I would see them. at

Vietnamese community celebrations in full military regalia and and they

were still trying to recreate South Vietnam in San Jose, California, which

would entail, whenever we were at one of these community gatherings,

that we sing the national anthem and salute the flag and, rehearse our

commitment to the anti communist cause.

So I’m very deeply empathetic to the kinds of emotions, that led to this,

that this was a generation of people, men and women, who felt that they

had lost their country because been betrayed by the communists, were

very angry and very bitter in a lot of ways, But, I’m also an outsider, so

I’m also very skeptical of many of their beliefs, many of their convictions,

their place in history, and so on.

And I wanted to write a novel, uh, that would not simply, um, venerate

the older generation and what they saw, but to cast them as you know,

complicated historical actors in their own drama. From an artistic

perspective, that’s very compelling. From the perspective of a community

that feels like it’s been underserved, under recognized, misrecognized,

distorted in various ways, they may not feel the same way about a story

that doesn’t idolize their history.

PHIL: Right, and I think especially if they haven’t finished or haven’t,

yeah, haven’t finished reading The Sympathizer, right,

VIET: They read The Sympathizer? Oh my

PHIL: Exactly, right? I don’t think it is translated in Vietnamese

VIET: It iis not translated into Vietnamese, and that’s a whole other

complicated story, because the Vietnamese American community,

Some of them think I’m a communist. Um, I’ve been told that, uh, quite

often. And yet, at the same time, the communist government thinks I’m an

anti communist, which is why they don’t allow The Sympathizer to be

published in Vietnam. So, because the novel tries to tell the truth from my

point of view, that truth does not easily reconcile with these orthodoxies

that are found among, in the Vietnamese communist side, and in the

Vietnamese anti communist side.

PHIL: Yeah, and we see the scene where the general puts on that full

regalia and the, the response that’s elicited by some of the, uh, the, the

women in the refugee camp, right?

VIET: That is a true story as far as I know, that there was a Vietnamese

general who was pelted by the refugee women, With fruit and vegetables

or garbage of various kinds because they were obviously mad, that this is

the outcome of the war that was waged. But even more than that, that

they were blaming this particular general for having fled the country.

Now this is based on reality, that, Nguyen Co Ky, the, the vice president

or premier of the South Vietnamese government in 1975, who was also an

Air Force officer, had gone on the radio saying in the final days, Stand to

your posts, resist the communists, fight back into the last man. And then

he got in a helicopter and flew to an American aircraft carrier.

Um, and certainly his character is one of the inspirations for the figure of

the General. So, on the one hand, there’s this intense nationalism and

fervent anti communism and the spirit for warfare and everything.

And as the character of Bon himself expresses in the novel, if these guys

were so intent on fighting the war, why didn’t they stay and fight to the

last man? That’s the contradiction he can’t live with.

PHIL: Right, right. And, and, and at the same time we see when the

general makes it into the United States, his sort of This role reversal that

happens, right? Um, especially as they’re kind of moving into this new

home in L. A. Um, before he opens the liquor store, uh, could you talk a

little bit about that, that dynamic between, uh, post resettlement, right?

Uh, between, um, some, sort of, some of the familiar roles in the, uh, in

now a Vietnamese American family.

VIET: These refugee exiles, um, the military and government types,

political types, they were, in charge of South Vietnam. They had the

power. They had the clout. They were at the top of the hierarchy.

And yet, most of them did not have any transferable Job skills. So when

they came to the United States, it didn’t matter if you were a Supreme

Court Justice or an Army general or whatever, you, those skills did not

apply, Bye. And so it was not uncommon for these men, uh, to experience

downward mobility and end up doing jobs that they thought were beneath

them, uh, while their wives.

On the other hand, uh. Often found upward mobility because their skills,

cooking or running enterprises and things like that, could be transferred

into the United States. In the case of my own family, my parents were, uh,

business people, so they had, I don’t know how much social prestige they

had in Vietnam, but in the United States they could totally recreate their

lives and even do better with the economic skills that they had.

So the General is forced to open a liquor store.

PHIL: I want to talk to you about the liquor store. Um, //there’s a lot of

imagery and a lot of, uh, you know, this is sort of, I think the, in the

series, the first place where Vietnamese American community post

refugee resettlement gather, right? It feels like an insider, there’s an

insider conversation going on at the same time that there is a sort of, uh,

maybe play on the American or mainstream trope of the South

Vietnamese as corrupt, um, corrupt soldiers, right? Uh, could you speak a

little bit to that?

VIET: I want to point out that when we were introduced to the liquor

store, the general, uh, takes the captain to the side and says, look at this

horrifying graffiti that’s been

PHIL: Oh, the image.

VIET: And that’s an image that is of a man getting shot in the head.

That’s drawn from the famous or infamous Eddie Adams photograph of

General Nguyen Ngoc Loan, who was actually in charge of Saigon’s

military police executing a Viet Cong guerrilla on the streets of Saigon

during the Tet Offensive. And that was a world famous image. that shook

up political sensibilities across the globe in regards to the conduct of the

war in Vietnam and helped to turn, uh, a considerable number of non

Vietnamese people against the South Vietnamese government.

Now, General Nguyen Ngoc Loan, uh, also fled as a refugee to the United

States and he opened up a pizza parlor.

PHIL: think in like the Northeast,

VIET: I think Virginia, I think, Virginia or Boston, and he never could

obviously escape from the legacy of that image. So that’s where the

reference is. And these Vietnamese refugees have been, uh, downwardly

mobilized, downwardly demoted into the role of small businessmen,

which obviously they find quite humiliating. And of course, uh, in the

liquor store, when we’re introduced to it, A new character appears, Sonny

the journalist, who’s also inspired by a real historical figure as well.

And, um, you know, that figure of the Vietnamese American journalist

who’s trying to Start a Vietnamese American newspaper industry and to

tell the truth and to report on the facts, this would come into conflict with

the South Vietnamese newspaper. Exiled political regime. Which did not

want the facts, did. he’s,

PHIL: he’s, He’s more of an immigrant than he is a refugee. A political

refugee.

VIET: Well, that’s right. He, he came as a international student along

with a captain in the 1960s. But unlike the captain stayed in the United

States, and this is true, by the time the Vietnamese refugees arrived on

mass in the summer of 1975, there 10s of 1000s of them, but there were

already hundreds of Vietnamese international students in the United

States.

And in the 1960s and 1970s, that was a divided community. There were

people who supported the South Vietnamese regime, and there were

people who were opposed to the South Vietnamese regime. There were

radicals and leftists and so on in this Vietnamese international student

community. Sonny is one of those. Who did not return to Vietnam but

stayed and essentially is becoming an immigrant or an American at this

point, a Vietnamese American. And he is somebody who’s been

politically out of step with this, this new influx of South Vietnamese

political and military exiles.

PHIL: Mm. Yeah. And it’s, it’s, you know, we’ve been talking about, I,

I’ve been thinking a lot about how this, this series, the book and sitting

right across from you talking about the show is very meta. Uh, I’m also

thinking about Bon and and the captain coming to the United States in

this like, uh, baby blue car. And he and there’s a line that he says, uh, that

that that film cowboy, right? And so there is already this, um, which is

which translates to, um, I thought you liked the cowboy movies, right? So

there is this sort of, um, Almost allure that the promise or the opportunity

of the American dream has that they’re also grappling with.

Um, as we, you know, kind of transition into talking about the Oriental

and perhaps professor hammers character. Um, I’m also thinking about

dude, do these particular refugees occupy the sort of my model minority

white adjacent space? Um, and is that strategic for them to be able to You

know, work around some of these, uh, this, this White sort of white or

American paternalism guilt, patriarchy.

VIET: I think it’s a very explicit theme in the novel, obviously, that, the

Vietnamese have gone from being these incomprehensible, figures in the

Vietnam War who were either the enemies or the allies of the United

States, but then they come to the United States and they, become

transformed, not, To being not just Vietnamese refugees, but into being

these Asian immigrants as well, which means that they’re already gonna

be subjected to all of these preconceptions that you just outlined about,

you know, Asians as a model minority and their function in the United

States.

And so, when the captain and Bolden are making that cross cultural

decision, country road trip, you know, it’s taking place against this,

mythical western landscape, and it does evoke the westerns and the

cowboy movies and everything. And, it’s not, this is not stated super

explicitly in the TV series or in the novel, but certainly when Vietnamese

refugees come into the United States, we are outnumbered. outsiders.

But our path to being insiders, to being citizens, is going to happen

against the backdrop of anti black racism, and anti indigenous racism, and

the acceptance of settler colonialism. so that you could be a refugee and a

citizen, All at the same time.

PHIL: And then we’re brought into Cal West College in the TV series.

Um, Occidental College in the book where we’re introduced to, uh,

Robert Downey Jr. again, playing the role of Professor Hammer. Uh, is,

uh, Does he feel real to you?

VIET: Oh, he feels very real. I mean, I think Robert Downey Jr. does a

great job in all of the roles.

PHIL: Right, because he felt real to me, being someone in, you know, in

academia to think, you know, maybe a little, quite exact, a little bit

exaggerated.

But I imagine that’s what happens behind those, those closed office doors.

VIET: Okay, let me just point out a real historical thing that happened to

me, uh, with a real Professor Hammer figure. Which is I was hired at

USC as a professor in 1997. And, uh, I met this other professor, an

anthropology professor, a white guy.

And every time I met him in the hallways, he would just give me this

look, and I would just get creeped out, you know. And, as it turned out,

this particular professor specialized in Asian studies, and then eventually,

uh, fled to Mexico, and was put on the top 10 wanted list by the FBI for

the things that he was doing with Southeast Asian boys when he was

going on his research trips.

So, whatever Professor Hammer represents as a satirical character, it’s not

as if these things did not happen in reality. And his particular

predilections, personal predilections, are fused with his political ideas and

with his methodological research and his whole view of the Orient.

And I also want to point out that, that, you know, the, the, there’s, there’s

an intense satire of so called Oriental studies that’s taking place through

him and through the name of his department.

But it was really the, the screenwriter for this episode, Nomi Iizuka, Who

put the words Asian American studies in the mouth of the professor like

“who are these Asian American studies people and what are they

threatening to do here? So, so scandalous.”

And I, that is not actually in the novel, and I thought that is brilliant. I

should have, I should have put it in

PHIL: because it’s happening at this time where Asian American studies,

which was founded in the sixties, uh, the late 60s, 68, 69, the third world

liberation front at San Francisco state and at UC Berkeley, um, students

were on strike and they had fought for there to be a third world college

that ended up being a, Uh, for most, for the most part, Departments of

Ethnic Studies.

VIET: 1975, when these refugees arrive, and, and, uh, the captain sees

Professor Hammer again on the cam on this college campus. In fact, that

is pretty much the turning point for the college radicals of the, of the

sixties at Berkeley, at UCLA, at San Francisco State. For, that’s the

turning point for when they start to get a toehold in the university.

Asian American Studies classes have been created. They’re starting to be

taught by these radical activists who are becoming assimilated into the

university. That’s exactly what Nomi is referring to in putting those words

in Professor Hammer’s mouth.

PHIL: And we are also introduced in that same department to Miss Mori,

who is played by Sandra Oh.

VIET: Oh, Sandra is lovely. She does a great job. She was always my

first choice for the part of Ms. Mori. But, um, the character of Miss Mori

is, is really, fascinating. I hope, very funny and very, um, you know,

feminist and very Asian American. And she’s in there to serve as the

voice of a Of a, of, a, of this Asian American feminist political

consciousness that is completely alien to Professor Hammer, but also a

little, quite strange to the captain himself who has to deal with it. grow

up, who has to change, who has to recognize some of his limitations that

Ms. Mori will be able to point out.

PHIL: Let’s talk about that via the naivety of our, of our captain, of our

dear captain. Um, because I think there are certain parts of the book.

Because it’s told from his perspective that, I mean, I don’t even know how

you really got there, but his naivety shows, right, and it, it, it changes

throughout the course of the novel.

Um, we get some flashbacks around the captain’s naivety and his, uh,

coming of age sexually. Um, in, um, How do I say it? Encephalopods

form. Um,

VIET: Squid! Squid! You can say it!

PHIL: insert squid emoji here? You know? Um, yeah, but the squid, uh,

you’ve, you’ve spoken a lot about the squid, but I’ve got to ask because it,

do you feel like the, the, the series did this, the squid scene justice?

<>

VIET: So, anybody who’s watched this episode realizes that our captain

loses his virginity to a dead squid. And I had a lot of fun writing that,

partly because it is a semi autobiographical experience.

And, it’s a reference also to Portnoy’s Complaint by Philip Roth from

1968, a very famous and popular and scandalous novel at the time, in

which Alex Portnoy, the very horny narrator of that book, basically

masturbates with anything he can get his hands on, including a slab of

liver from the family fridge.

Um, and then after he finishes his business with that slab of liver, he puts

it down. back in the fridge where the family will then consume it for

dinner later that night. And when I read that novel I was 12 or 13, it’s all I

would remember for the next 20 or 30 years. And all I could think about

was, wow, that’s gross.

They eat liver for dinner.

PHIL: okay. I was like, oh, what was gross?

VIET: Yeah, but we ate liver growing up, so to me, it was like perfectly

normal. I totally identified with this scene. And so I’m so delighted that

Director Park and Don McKellar and Nomi Iizuka found a way to include

That very graphic scene in this episode.

PHIL: Yeah, and I think for the captain, for the captain as we’re making

our way through this episode, he’s, he’s kind of got game in using the, the

scene to, uh, to woo Miss Mori, right? Or to, to get them on the same

VIET: So lemme point out something really crucial. According to

amazon.com and Goodreads reviews, I’d probably read lose about one or

2 of readers right at this moment at the squid masturbation scene because

that percentage of readers thinks this is so gross, how can you continue

Uh, and then of course if you read the end of the scene in the novel, the

line that the captain says is, yes, you know, “if only murder and massacre

made us mumble as much as the word masturbation.”

That’s the point, okay? Um, we’re willing to accept all these horrifying

things that happen because our nation state says it’s okay for us to kill

people, but masturbating with a squid? Off limits. Let’s ban books at this

point. Um, and the the combination of sex and violence is a theme that

runs throughout the entire novel and the TV series, so if you, if you watch

the series all the way to the end, there will be a very crucial way that this

thread continues, but the captain doesn’t get it. Okay. The captain only

gets, un, you said naivete, the captain only understands part of this. That

line about murder. Massacre. Masturbation.

He does not yet realize that he himself is not just a critic, he is also deeply

implicated in this nexus of sex and violence and the objectification of

women and squid. And it’s Miss Mori who will be part of the puncturing

of that consciousness, but the rest of the plot will force the Captain to, to

fully confront how deeply invested he is as a man. in this system of

objectification and violence.

PHIL: And it’s, it’s something that he denies from the first episode when

he’s sent to, um, the United States by, uh, his dear blood brother, uh, and,

uh, overseer, uh, Man, right?

Um, that he, he is in love with American, American culture, right? And

we start to see that, that love in all of its complicated ways, uh, unravel,

uh, in the, in this particular episode. Um, well, Viet, thank you so much.

You know, we’re, um, Here at the end of episode two for the companion

podcast of The Sympathizer.

Uh, and in future episodes, we’ll dig a little bit deeper into all of the, uh,

different depths of, um, sex, violence, murder, uh, mas turbation, and

murder.

VIET: Glad we could end with a squid, Philip.

Interview OUT VIET

And that’s it for us today. Thank you to Amanda Burrell, Hoa Xuande and

Viet Thanh Nguyen for their time and insight. We’ll see you all next time

when we dive into episode three with Academy Award winning actor and

executive producer, Robert Downey Jr., Prosthetic effects designer, Vincent

Van Dyke, and returning guests, Don McKellar, Hoa Xuande, and Viet

Thanh Nguyen. See you then. Stream new episodes of HBO’s original

limited series, The Sympathizer, Sundays, exclusively on Max. And

subscribe and listen to the podcast after every episode of the show on Max

and wherever you get your podcasts.

CREDITS