Viet Thanh Nguyen reviews Erika Lee’s The Making of Asian America: A History. Originally posted by the Los Angeles Times on September 3, 2015.

Asian Americans are the fastest-growing minority population in the United States. They have been living in this country in significant numbers since Chinese immigrants came hunting for gold in the middle of the 19th century. But even before then, Asians migrated to the Americas, beginning in the 1500s, as slaves, sailors, merchants, explorers and adventurers. Asian migrants have come to the Americas from many different countries, spoken dozens of languages, identified themselves across a wide range of ethnicities and religions, and intermarried with each other and with people of other backgrounds. Some have succeeded, and some have failed; some have stayed, and some have left.

There is no one way to define or identify a population as complex as what we have come to call “Asian Americans,” and yet in the popular American imagination, Asian Americans tend to be seen in simple ways. They are the model minority, the natural-born geniuses who work hard and quietly, making no trouble. Or they are the Yellow Peril, indistinguishable from Asians overseas, threatening to take all the college admission slots and overwhelm American borders with their bodies or the things they make in their Asian factories.

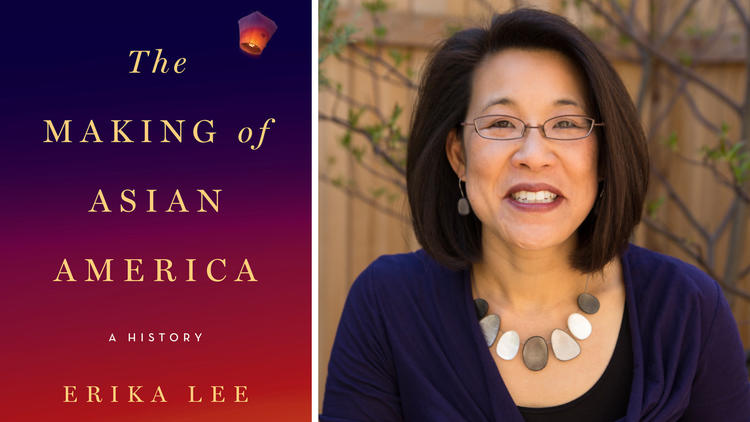

Erika Lee’s new history, “The Making of Asian America,” takes these simple — and dare I say racist — notions of who Asian Americans are and contrasts them with their rich, complicated stories and their struggles to become a part of the United States and other American countries. Lee’s monumental work spans 500 years and extends from Canada through the United States to several Latin American countries, notably Mexico, Brazil and Peru. She manages the sweep of her history and its multitudes deftly, drawing on archival research and the significant body of historical work done by many predecessors.

A professor of history at the University of Minnesota, Lee handles her scholarly materials with grace, never overwhelming the reader with too many facts or incidents. She tells an American story familiar to anyone who has read Walt Whitman, seeking to capture America in all its diversity and difference, while at the same time pleading for America to realize its democratic potential.

The “Asian American community … uniquely captures the story of America,” she writes. “Theirs is a history of immigrant dreams, American realities, and global connections that has helped to make the United States what it is today.”

But unlike the other major work of Asian American history written for a larger audience, Ronald Takaki’s 1989 “Strangers From a Different Shore,” Lee emphasizes not only the national dimension of Asian American experiences but also their transnational contexts. Thus, she begins her history with two chapters on “los chinos in New Spain and Asians in Early America” and “coolies,” the term the British used to describe the Indian, Chinese and other Asian labor that they used and abused in their colonies. The United States then adapted these British — and Spanish — migration routes and practices of exploited labor when it needed cheap workers in the 19th century.

The subsequent story told by Lee is both heroic and tragic, as Asian migrants came to the United States and Hawaii in successive ethnic waves through the early 20th century — Chinese, Japanese, Indian, Korean — only to be labeled by white nativists as racial, economic and sexual threats. Nativist, racist movements subjected each of these Asian populations to violence, segregation and exploitation. Eventually they succeeded in excluding Asians from immigration, beginning with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. But the migrants persevered, using any legal and illegal means available to them. They went to court to defend themselves, and they also subverted the nation’s attempts to shut them out of the country by becoming undocumented migrants. The exclusion era would not end until 1965, when the U.S. finally eliminated racial quotas for immigration.

Other migrants came to the United States as a consequence of the wars that the U.S. waged in the Philippines, Korea, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Although Lee describes these acts as “U.S. imperialism,” she refrains from saying that they may be structurally a part of American capitalism and culture, an inevitable outcome of expansionist and racist impulses in the American character. In that sense, her history is one for the age of Obama, a man who talks about the flaws of the United States but insists on the perfectibility of the Union. For Lee, Asian Americans, for all that they have endured in terms of racist exclusion and economic exploitation, embody America’s potential because they insist on holding the United States accountable.

Lee’s narrative concludes by emphasizing how the racist treatment of Asian Americans, symbolized in things like exclusion laws, internment camps, hate crimes and racial profiling, have led to the creation of Asian American activists who seek not only justice for themselves but others. Powerful Asian American stories like these are inspiring, and Lee herself does them justice in a book that is long overdue.

::

The Making of Asian America: A History

Erika Lee

Simon & Schuster: 528 pp., $29.95

Nguyen is associate professor of English and American Studies and Ethnicity at USC and author of “The Sympathizer.”